Małaszewicze-Brest border crossing main bottleneck on New Silk Road

While volumes on the New Silk Road are rapidly increasing, the route also has some serious bottlenecks, such as the Małaszewicze-Brest border crossing, connecting Poland and Belarus on the most popular railway route between Europe and China. This was one of the main conclusions at the Silk Road Summit, Gateway Poland held in Wroclaw last week.

“When the railway connection between Europe and China was first introduced as a viable alternative to road and sea freight, the proposed transit time was nine days”, Krzysztof Szarkowski, Intermodal/Rail Manager at DHL Freight uttered. At the moment, a journey from Duisburg in Germany to Chongqing on the east coast of China takes 14-16 days. These are impressive transit times, considering that the first train on this route took 25 days to reach its destination. However, they are not what they are supposed to be.

Delays at the border are the main reason for the extended journey time, many agree with the Malzewicze-Brest border crossing being the main bottleneck. In a regular trip, trains wait at the border for two to three days. This easily becomes five days, while waiting times can also extent into weeks. “I know of a company that is suffering a delay of three weeks at the moment”, said Juliusz Skurewicz from the Polish International Freight Forwarders Association. “The average delay of Polish rail freight traffic in 2017 exceeded ten hours; we saw an average punctuality of 34 per cent. These are poor results.”

Infrastructure or management

Poor infrastructure has long been named as the common source of the bottleneck on the vital corridor. “Poland needs to invest in more border crossings, to ease traffic at the Małaszewicze-Brest border point”, said Maciej Mastalerski, Managing Director of InterRail Poland. The country is the biggest beneficiary of the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF), with Polskie Linie Kolejowe (PKP PLK), the Polish national rail infrastructure manager receiving the bulk share – 66 billion Euros – to improve the national infrastructure. “This is only evidence that there is a shared understanding of the importance of this infrastructure”, argued Skurewicz.

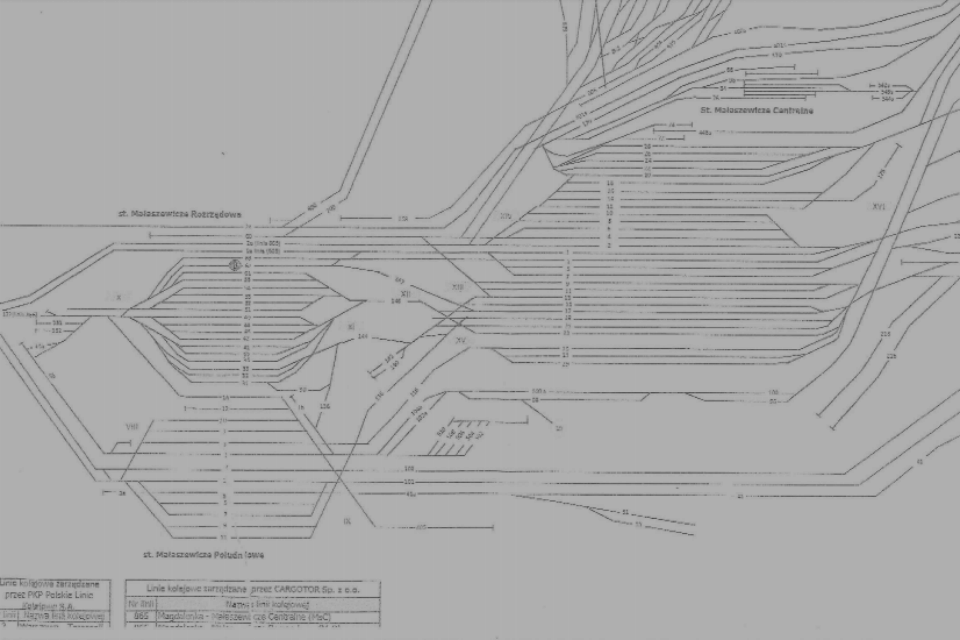

But according to Szarkowski, there is an organisational problem, rather than an infrastructural one. “There are four terminals, each with the capacity to handle ten trains per day. Some of them only handle one or two trains per day; some of them do not even handle Eurasian traffic.” His argument is underlined when Peter Plewa, Executive Board of Duisport, displays a graphic of the facility on the Małaszewicze side of the border. “This looks just like any other important railway terminal. There is enough space to operate, but if operations are not managed efficiently, they will not be improved”, he said.

Custom procedures

“Custom officials on two sides of the border do not communicate in the same language, or keep the same administration”, Plewa continues. Indeed, logistics companies recognise the stories of dreadful border procedures, where documentation is often ‘not correct’. “For example, there may be discrepancy with the load amount, sometimes in the third digit after the comma. The third digit after the comma is not really important, also not for them. This is just about who is right, about showcasing power.”

Digitalisation could serve the custom procedure, however, there are currently no efforts undertaken towards such development. “As a forwarder, we receive documentation of the cargo per email, before making the journey. But we still face these issues. There are many different companies, and many different railways involved. There is no easy solution”, said Mastalerski.

Simplified procedures

Apart from customs, other factors contribute to the extended transit times. “Take the shunting for example”, Plewa said. “Who is managing the shunting procedure? The company that owns the wagons. There are many different companies, all operating their own private wagon. If this procedure was to be neutralised, volume handling could be increased by 20-30 per cent”, he argues.

With so many parties involved, the question arises who could actually change the situation in order to improve transit times at the border. This is a good question, said Szarkowski, drawing upon an example where a solution in the shape of a scanner, has until now not resulted in any improvements. “This was supposed to ease custom procedures, however, nothing changed. Trains are still stopped by customs, and wait for hours and hours for the same procedure as can be done by the scanner, just because the infrastructure manager decided that a train must stop at that point.

“Added to this, the custom stop on the Polish side of the border is 900 meters, although trains from the CIS countries are 1,200 meters in lenght. These trains must be split at this point. But if they drove directly to the scanner and then to the terminal, there would be no need for dividing trains.”

Expectations

Acording to Mastalerski, there is little chance that something will change in the near future. “We have been operating at this border crossing for 26 years, and nothing has changed so far.” In his view, the only solution is in alternative border crossings to carry the largely increased volumes passing through Poland. As such, the Kaliningrad route has great potential, he argues. The Russian enclave lies between Poland and Lithuania, and re-routes freight trains on a 9,559 kilometer journey through Lithuania to continue on the Trans-Siberian railway through Belarus, Russia, and Kazakhstan.

Skurewicz is more positive about the potential of the Małaszewicze-Brest border crossing. “There is certainly work being done to improve the situation”, he explains. As a freight forwarders association, his company is involved in this development. “Obviously, the current terminal is not a solution for the large volumes handled at this border crossing, this requires a more modern, and developed terminal.